2025-1217-2238 gdc - Huddle up - Making the SPOILER of INSIDE

Slip-box

To be fleeting notes

Fleeting

To be literature notes (Understanding)

L-Origin

围聚一堂:回顾《 INSIDE 》杂志“怪物”一书的跨学科创作历程

引言:围成一圈的六年起源

在游戏_《INSIDE》的高潮部分_,出现了一个令人难忘也令人不安的生物:Huddle。它被描述为“由肌肉、脂肪、皮肤和骨骼组成的复合体,完全是人形的”,远非传统电子游戏中的反派角色可比。它的最终形态是Playdead工作室几乎所有成员参与的一项历时六年、高度迭代且跨学科实验的成果。Huddle并非简单的设计,而是在不断的艺术探索和技术创新循环中,一层层构建而成。

本次回顾展将深入剖析这一非凡的创作过程,追溯这只生物从最初的概念图到最终成为完全模拟、栩栩如生的怪物的历程。我们将探讨概念动画(奠定了整体愿景)、核心物理编程(构建了其变幻莫测的灵魂)、程序化游戏系统(赋予其生命幻觉)以及视觉特效着色(最终将各个部分粘合成一个浑然一体的整体)各自独特的贡献。

1. 概念基础:从静态草图到动态愿景

在一个漫长而复杂的开发周期中,尽早确立清晰的艺术和行为愿景至关重要,即便实现愿景的技术手段尚未确定。Huddle 的概念阶段并非旨在创建最终成果,而是为了确立一个“远景目标”——一个切实可行的目标,它将在未来几年激励和指引整个团队。

“围成一圈”的起源可以追溯到首席美术师莫顿·TD·斯滕斯加德的一幅开创性的概念艺术图。这幅内部被称为 “土豆图”的草图, 成为了建模、着色和光照等关键决策的权威参考,不仅影响了“围成一圈”的建模,也影响了整个游戏。虽然这幅静态图像在视觉上独具特色,但却几乎没有展现任何动态效果。动画师安德烈亚斯·诺曼·科恩的任务就是将这幅草图转化为动态画面,并从各种来源汲取灵感:

• 《幽灵公主》****: 被妖魔化的野猪神那戈是“哈德尔”攻击性、变形性和目标导向性的重要参考。这种生物能够自发地调整自身,在需要的地方生成肢体,这一概念是其核心灵感来源。

• Gish : 这款以物理引擎驱动的独立游戏为Huddle的基本特性——柔软可变形——提供了蓝图。它能够挤过狭小缝隙的能力直接影响了Huddle的设计。

•人群冲浪: 这种比喻启发了该生物众多肢体的行为。它代表了一种“主题混合体”,一群个体拥有共同的目标,但其内部运动却相互冲突——有些肢体在提供帮助,有些在抵抗,还有一些似乎想要摧毁整个体系。

为了快速探索这些想法,科恩搭建了一个简单的骨骼绑定系统,包含四根脊椎骨、大约20个反向运动学点以及一系列自由移动的肢体。这使得他能够迅速制作40个概念动画——他现在回想起来觉得这个过程“非常尴尬”——这些动画在技术基础搭建完成之前就确立了生物的行为模式。这些早期的探索定义了关键时刻和特征:

•它的最初蹒跚步伐是通过音效设计实现的,音效设计来源于 “浑身油腻的裸体人被大块肉抽打”的录音。

•为了赋予游戏生命力,开发者探索了各种闲散行为,包括尿尿、抓挠以及内心冲突等。其中一个想法——鸟儿仰面落地——在早期测试中萌生,并在六年后的最终版游戏森林场景中得以实现。

•关键的环境交互被制作成原型,例如抬起一个大箱子和穿过狭窄的缝隙。这一阶段还产生了最初的动画,为最终游戏中扣人心弦的钟摆场景提供了灵感。

虽然最终产品中没有使用任何这些关键帧动画,但它们的影响却十分深远。它们提供了至关重要的概念验证和共同愿景,极大地鼓舞了编程和美术团队。早在人们知道如何实现之前,它们就回答了“这东西应该是什么_感觉_?”这个问题,为随后复杂的技术模拟奠定了基础。

2. 核心工程:以物理为基础

概念动画成功地定义了“围堵”的预期行为,但也清楚地表明,传统的、关键帧动画方法行不通。团队做出了一个关键的决定,将思路从“如何制作‘围堵’的动画”转向“如何模拟它”。这种转向以物理为核心的策略对于实现最初设想中所需的涌现式、不可预测且复杂的行为至关重要。

最终的Huddle并非传统意义上的动画。它是一个蒙皮网格,其骨骼直接绑定到一组动态物体上,这些物体由Thomas Cole开发的自定义物理引擎驱动。每一帧,Huddle的核心都会读取并分析周围环境,生成大量的内部脉冲,并将它们同步回物理引擎。这个自定义模型由几个不同的、相互作用的组件构成:

•动态物体: 底层由26 个刚体组成,这些刚体 具有生命并受物理引擎控制。它们构成了生物体的基本物理质量。

•内部骨骼: 内部骨骼的平行结构缓存动态物体的属性(位置、速度等)。这一层负责累积内部脉冲,然后将这些脉冲反馈到物理模拟中。

•邻接图:

◦启动时,动态物体最初放置在一个球体上,并建立一个邻接图,用起到 ** 弹簧作用的边连接最近的相邻内部骨骼**。

这些弹簧的目标_长度_会根据核心的整体尺寸和高度不断变形。这使得生物能够逼真地伸展、挤压和扭曲身体以应对外力 。

•脊椎骨:

◦两根中央脊椎骨不仅受物理定律驱动,还受逻辑和动画原理驱动。它们充当宏观层面的控制系统。

每根脊椎骨都会影响一组内部骨骼,迫使它们跟随其整体运动。这一关键功能使得游戏逻辑能够引导群体的整体运动,有效地“绕过物理定律”来引导模拟,而不会直接干预物理过程。

一项具体的技术挑战凸显了这套系统的精妙之处:如何让Huddle在跌倒后重新站起来。简单地将脊柱旋转到垂直位置会显得很不自然,甚至“有点傻”。解决方案是在运行时重新配置脊柱骨骼,使整个内部结构以更自然的方式垂直升起。为了避免在重新配置过程中出现突兀的视觉“突变”,团队巧妙地将内部网格的目标边缘长度在多个帧中混合,从而掩盖了过渡,并保持了生物逼真的物理特性。

最终,Huddle 的核心是一个由众多独立系统构成的复杂网络——逻辑状态、玩家控制输入和辅助系统——所有这些系统都将信号输入到一个中央的、由物理引擎驱动的结构中。这种架构使得最终结果极易产生不可预测的涌现行为,确保玩家与 Huddle 的每一次互动都独一无二。然而,这个错综复杂、不可见的核心仅仅是成功的一半;下一步是赋予它能够与世界互动的实体肢体。

3. 生命的幻觉:程序化肢体与游戏玩法的融合

虽然物理引擎提供了动态且厚重的运动,但在视觉上,它看起来却像一个不自然的“漂浮物”。为了说明这个问题,游戏玩法程序员索伦·特劳特纳·马德森举了一个简单的例子:在一张鸟的图片上画两条粗糙的树枝状手臂,正如他所说,“它突然就变成了完全不同的生物。” 下一个关键的开发阶段就是对Huddle进行同样的改造——通过巧妙的程序生成系统来模拟肢体的自主运动,从而将抽象的物理效果与现实联系_起来_。

马德森的任务很明确:在不改动不断演进的核心物理模型的前提下,为Huddle添加一层薄薄的视觉效果,使其拥有四肢。解决方案是将Huddle的肢体视为独立的网格,在运行时连接起来,形成一个复合生物体。

•六条固定腿连接到核心底部的物理球上,负责运动。

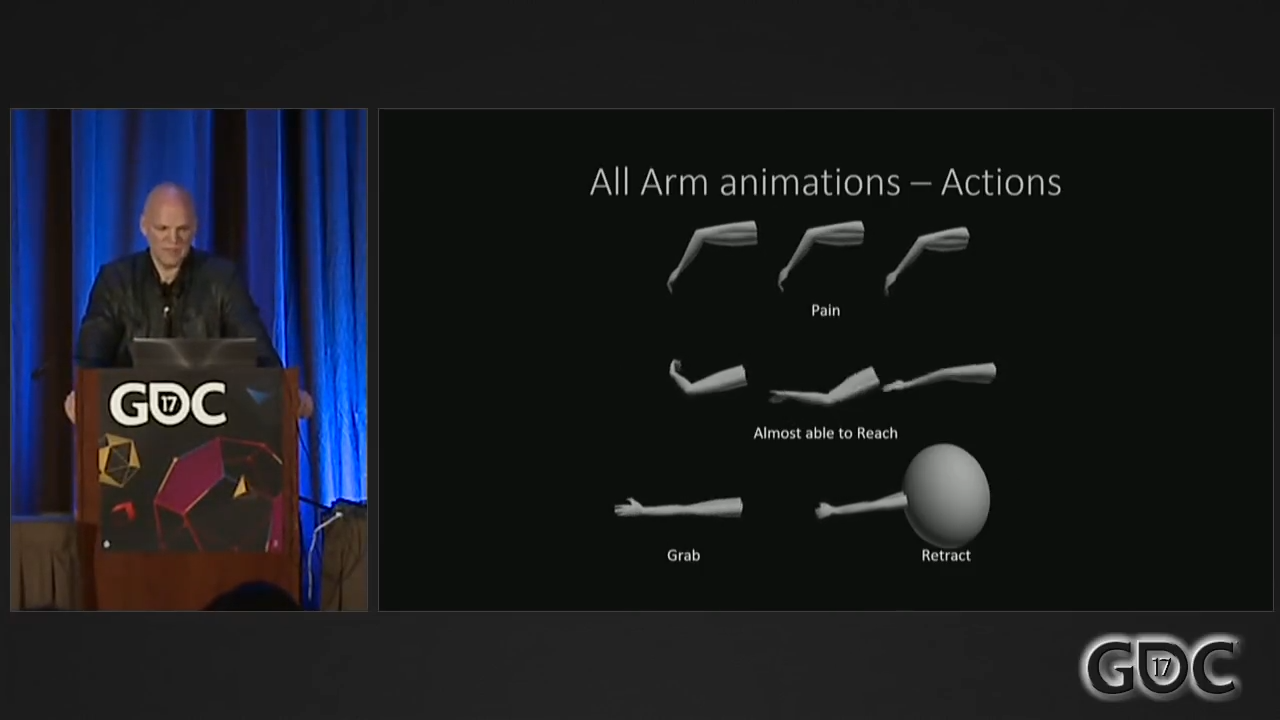

•顶部设有六个固定臂。当 Huddle 旋转时,它们会重新排列,以保持一致且清晰的轮廓。

•许多纯粹视觉上的身体部位(头部、躯干)附着在正面,增加了次要的运动感和内在的生命感。

•几个通常隐藏在物体内部的动态机械臂可以伸出来帮助抓取和与物体互动。

用于控制腿部动画的系统是一个精妙的“谎言”,一个看似简单却极具迷惑性的解决方案。马德森承认,由于其简单性,他“有点不好意思”展示它。该系统仅依赖于四个跑步动画(两个向前,两个向后)。其算法堪称优雅高效设计的典范:

1.从腿部在核心上的连接点发射的射线确定精确的地面位置。

2.跑步动画是根据腿部与地面当前位置的距离进行混合的。

3.父物理体的速度直接映射到跑步循环的动画速度,使腿部的运动与核心的动量完美匹配**。**

4.附加逻辑处理停止时过渡到稳定姿势、同步不同步态(行走与奔跑)的腿部位置,以及冻结动画以在光滑表面上创造逼真的滑动效果。

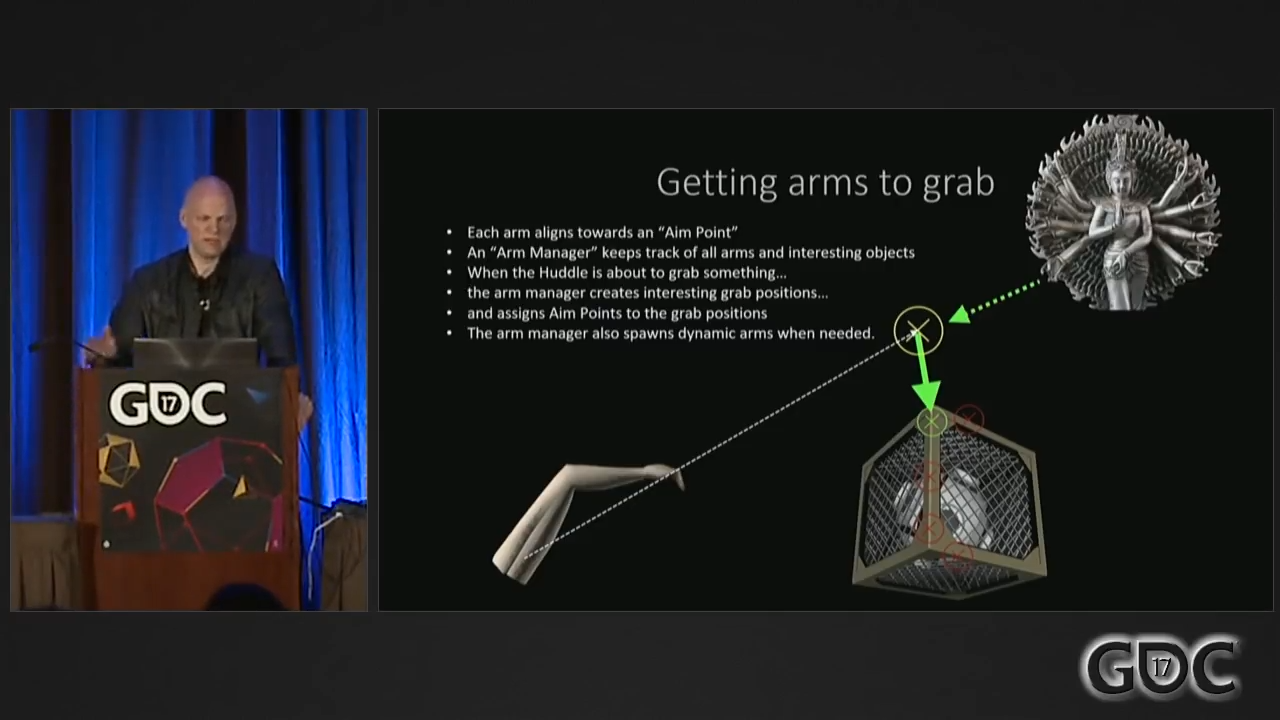

类似的程序方法也适用于机械臂,它们负责抓取物体并与环境互动。这由“瞄准点”系统管理:

•每个手臂都渴望到达一个在群体中漂浮的自主 “目标点” 。

•中央 “机械臂管理器” 识别场景中感兴趣的物体,例如箱子,并将这些瞄准点分配给该物体上的特定抓取位置。

•当机械臂的瞄准点足够接近目标时,机械臂会播放抓取动画并抓住目标。这使得静态和动态机械臂能够逼真地抓取、握持和攀爬物体,将简单的物理交互转化为看似深思熟虑、智能的动作。

这种程序化方法之所以取得巨大成功,正是因为它巧妙地解决了棘手的限制。复杂而逼真的运动效果,实际上是由一个简单的视觉系统叠加在物理模拟之上而创造出来的,两者互不干扰。这体现了Playdead开发理念的核心原则:“通常情况下,我们会根据所需的游戏玩法对Huddle进行尽可能多的调整;如果调整幅度不够,我们就移除该玩法,并开发出其他系统能够正常运行的玩法。” 最终的挑战在于,如何让这些原本各自独立运动的部件,在视觉和感觉上都像是一个统一的整体。

4. 着色器作为粘合剂:统一一个怪物

最终也是或许最为关键的挑战,是将Huddle的各个分散元素——核心物理网格、程序生成的四肢和装饰性的身体部位——在视觉上统一起来,形成一个整体。这项任务落在了Mikkel Svendsen的着色器工作上,他就像“着色器胶水”一样,将这些独立的几何体融合为一个怪诞的生物体。

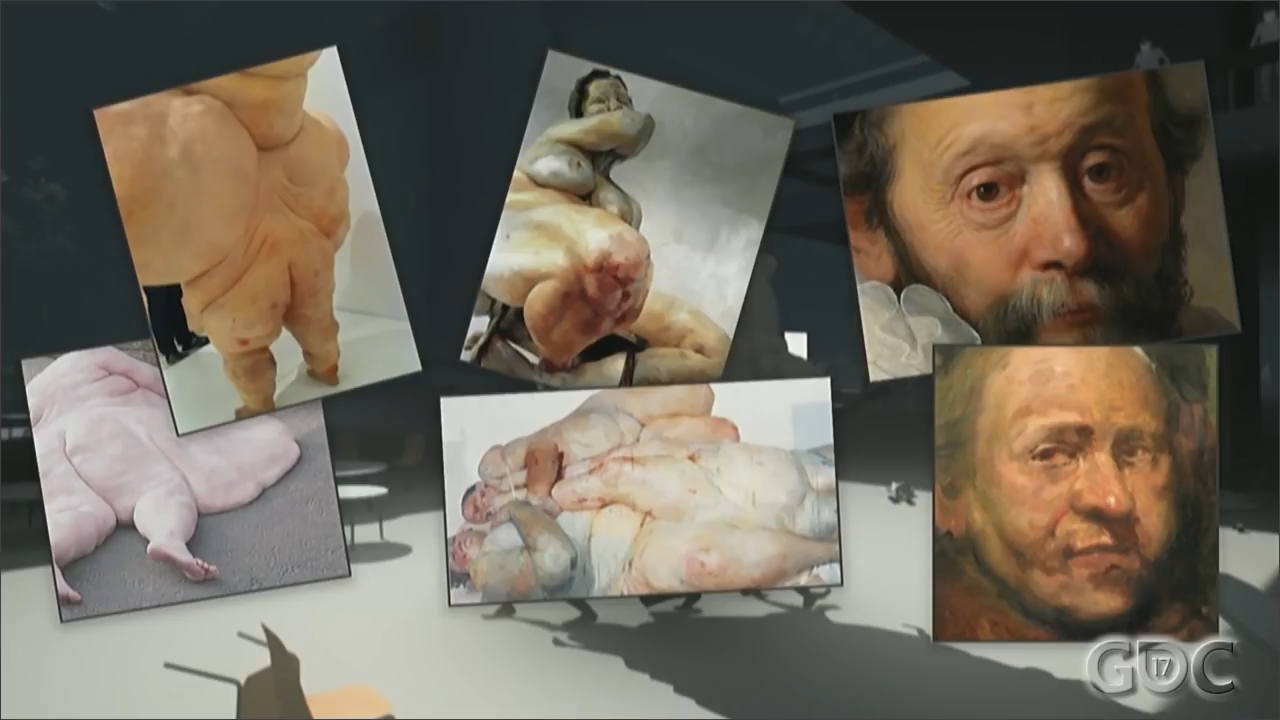

Huddle表面设计的艺术灵感源于对比鲜明的元素。约翰·艾萨克斯(John Isaacs)凹凸不平、肉感十足的雕塑作品为造型提供了参考,而伦勃朗(Rembrandt) 和珍妮·萨维尔(Jenny Saville)画作中色彩丰富、层次分明的肤色则启发了其呈现出一种有机而复杂的外观,避免了简单的粉红色调。

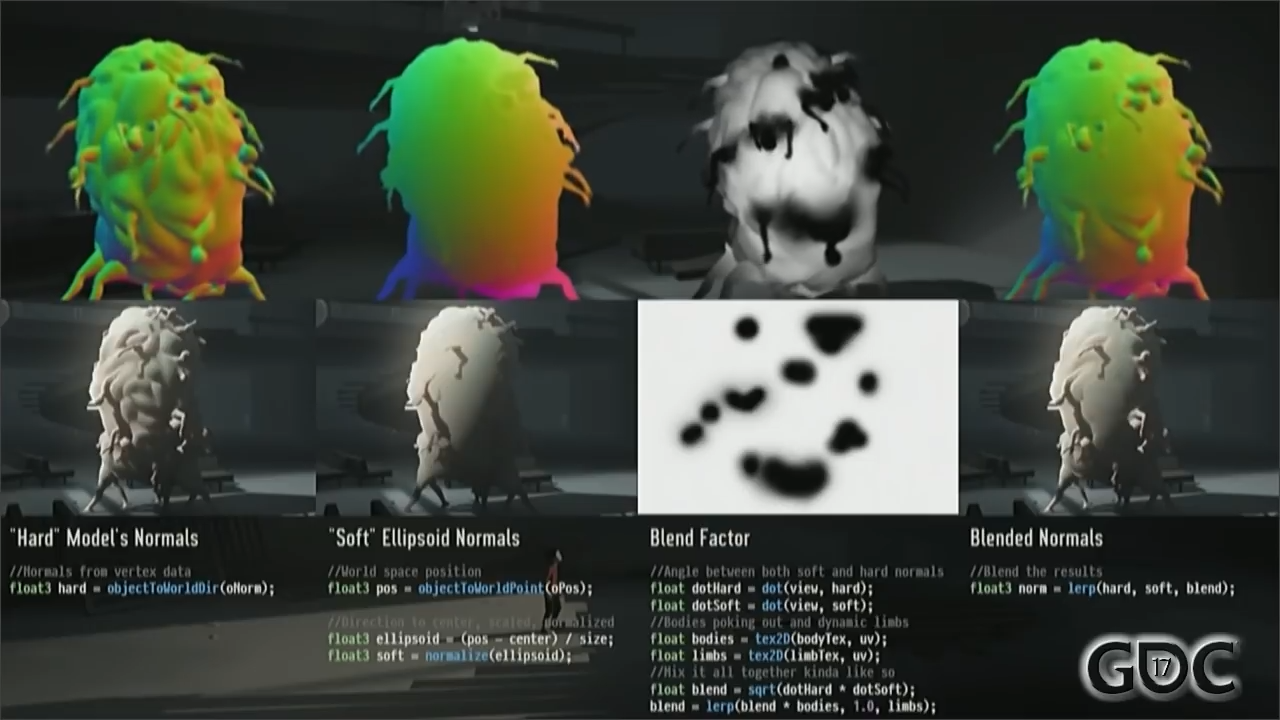

这一愿景是通过一套复杂的多层着色流程实现的,每项技术都起到将各个部分粘合在一起的作用:

•普通模式:混合硬模式和软模式

为了将坚硬的四肢与柔软的躯干连接起来,着色器将模型的硬边法线与柔和的球形投影法线混合。这项技术通过保留手指和脚部的细节来消除接缝,同时确保主体感觉像是一个单一、模糊且富有血肉的整体。

•光照和遮挡:营造景深

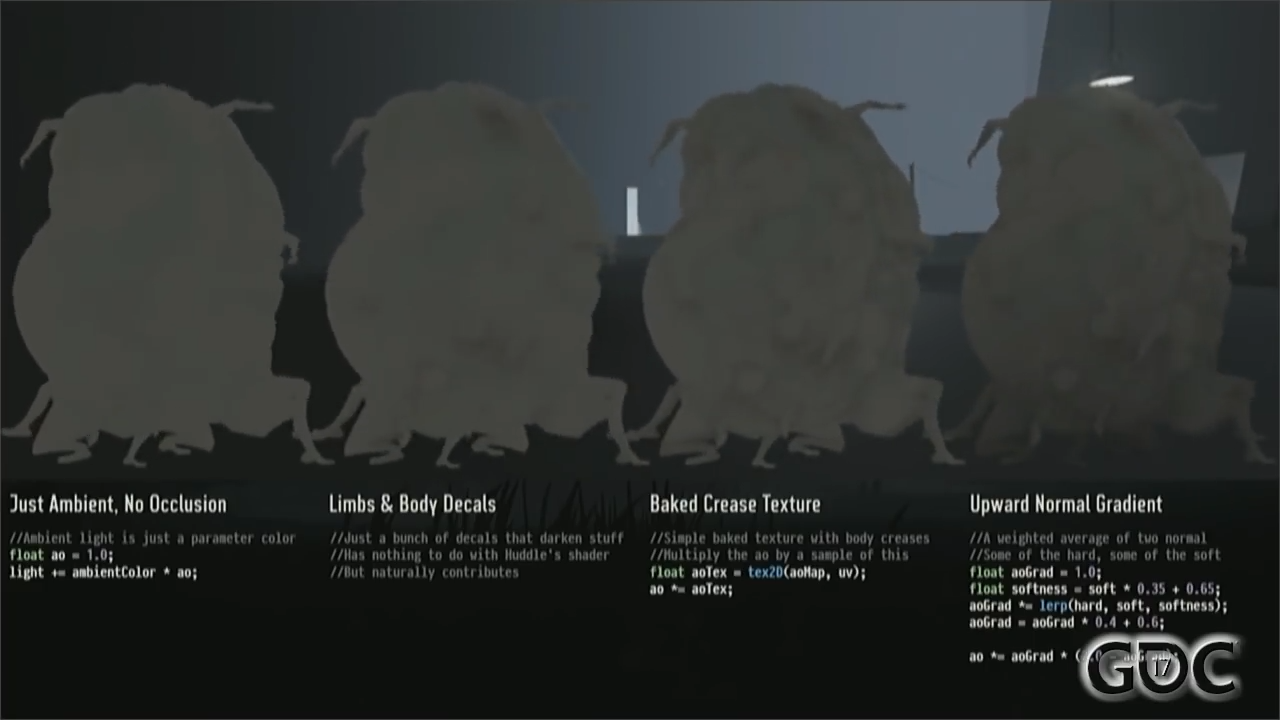

◦环境光确保可见性,叠加AO 贴花以减少光线,烘焙褶皱纹理以增强清晰度,以及至关重要的垂直渐变,从上到下产生自遮挡,使庞大的形体更加稳固。

•漫射光:特色与风格

◦自定义照明模型包括指数色调映射,以防止强光冲淡细节;轮廓光,用于分离;模拟背光效果(内部称为“粗糙度”);以及平滑的卡通风格阶梯,以增强对比度。

•高光:模拟湿润感

◦高光完全是“假的”。它并非由场景灯光生成,而是由一个硬编码的虚假光照方向(顶部、背面、侧面)产生。这个虚假高光随后会被实际的漫反射光遮蔽,确保它只出现在生物体被照亮的地方。为了营造出油腻腻的“周六烤鸡”效果,只在这个高光层应用了一张**“鸡皮”法线贴图。**

•地下散射:深入观察

一种简单却高效的次表面散射(SSS)方法赋予了生物肉质般的半透明效果。它使用红色着色的光照缓冲区进行四次螺旋模糊采样。为了解决常见的光线溢出问题(例如,从手到胸部,或从地板到身体),每个采样点都会与深度缓冲区和“聚集模板缓冲区”进行验证,以确保其采样点确实来自生物本身。

除了基础外观之外,还创建了一个动态表面特效系统,以视觉方式反映游戏过程中的损坏情况。一个脚本会“监听”核心中艺术家 “最喜欢的九个刚体”上的碰撞或触发事件。这些CPU端数据(例如,“这个部件被起重机撞击”或“这个部件靠近火源”)随后会被GPU收集,以创建一个低频遮罩,实时混合瘀伤、烧伤或血液纹理。

这些着色技术巧妙地融合在一起,掩盖了各个独立几何部件、物理对象和程序系统之间的接缝。这种着色器粘合剂将一系列机械组件转化为一个单一、逼真且令人不安的生物实体。

结论:合作催生未来

“Huddle”项目有力地证明了长期、迭代和深度协作的设计所蕴含的创造潜力。它历经六年,从一张静态图纸蜕变为一个鲜活的实体,展现了艺术构想与技术执行密不可分的历程。

一切始于一张基础性的“土豆草图”和概念动画,它们勾勒出清晰的愿景。随后,这一愿景并非通过传统方法实现,而是通过构建一个核心物理模拟系统,赋予这个生物难以捉摸的灵魂。接着,系统巧妙地赋予其生命幻象,通过程序生成的肢体,使其看起来像是在奔跑、攀爬和抓取,并带有某种意图。最后,一个复杂的多层着色器如同粘合剂,将这些分散的系统统一起来,形成一个单一、连贯而又怪诞的有机体。

Huddle 的最终角色并非出自一人之手,也非出自单一学科。相反,它是近十年来众多不同领域专家构建的系统之间复杂且有时难以预测的相互作用的产物。它是一个真正的涌现怪物,诞生于整个工作室的集体想象力。

Huddle Up: A Retrospective on the Interdisciplinary Creation of INSIDE's Monstrosity

Introduction: The Six-Year Genesis of the Huddle

At the climax of the game INSIDE lies one of its most memorable and unsettling creations: the Huddle. Described as a "compound, fully humanoid blob of muscle, fat, skin, and bones," this creature is far more than a conventional video game antagonist. Its final form is the result of a six-year, highly iterative, and deeply interdisciplinary experiment that involved nearly every member of the Playdead studio. The Huddle was not simply designed; it was grown, layer by layer, through a constant cycle of artistic exploration and technical innovation.

This retrospective deconstructs that remarkable process, tracing the creature's journey from a single piece of concept art to a fully simulated, living monstrosity. We will examine the distinct contributions from conceptual animation, which set the vision; core physics programming, which built its unpredictable soul; procedural gameplay systems, which gave it the illusion of life; and visual effects shading, which served as the final glue to unify its disparate parts into a cohesive whole.

1. Conceptual Foundations: From a Static Sketch to a Moving Vision

In a long and complex development cycle, establishing a clear artistic and behavioral vision early on is paramount, even when the technical means to achieve it are not yet defined. The conceptual phase for the Huddle was not about creating final assets, but about establishing a "spot on the horizon"—a tangible goal that would inspire and guide the entire team for the years to come.

The Huddle's origin can be traced back to a single, seminal piece of concept art by lead artist Morton T.D. Stensgaard. This drawing, internally referred to as the "potato drawing," became the definitive guiding reference for critical decisions on modeling, shading, and lighting, not just for the Huddle, but for the entire game. While visually distinctive, the static image offered little hint of motion. It fell to animator Andreas Norman Cohen to translate this sketch into a moving vision, drawing inspiration from a diverse set of sources:

- Princess Mononoke: The demonized boar god, Nago, served as a key reference for the Huddle's aggressive, morphing, and goal-oriented nature. The idea that a creature could spontaneously recalibrate its body, spawning a limb where needed, was a core inspiration.

- Gish: The physics-driven indie game provided the blueprint for the Huddle's fundamental squishy and deformable character. Its ability to squeeze through small gaps was a direct influence.

- Crowd Surfing: This analogy informed the behavior of the creature's many limbs. It represents a "mixture of motifs" where a cluster of individuals shares a common goal, but with conflicting internal motions—some limbs helping, some resisting, and some seemingly trying to tear the whole thing down.

To rapidly explore these ideas, Cohen built a simple rig with four spine bones, around 20 IK points, and an assortment of free-floating limbs. This allowed for the quick production of 40 concept animations—a process he now finds "really embarrassing" to look back on—that established the creature's behavioral vocabulary long before the technical foundation was built. These early explorations defined key moments and characteristics:

- Its first stumbling steps were brought to life with sound design sourced from recordings of "oily naked people getting slapped with large pieces of meat."

- Idle activities were explored to give it a life of its own, including concepts like peeing on itself, scratching, and moments of internal conflict. One idea, a bird landing on its back, was conceived in these early tests and implemented six years later in the final game's forest scene.

- Crucial environmental interactions were prototyped, such as lifting a large crate and pushing through a narrow gap. This phase also produced the initial animation that inspired the final game's dramatic pendulum scene.

While not a single one of these keyframed animations was used in the final product, their impact was profound. They provided a crucial proof-of-concept and a shared vision that galvanized the programming and art teams. They answered the question "What should this thing feel like?" long before anyone knew how to build it, setting the stage for the complex technical simulation that would follow.

2. Engineering the Core: A Physics-Driven Foundation

The conceptual animations successfully defined the Huddle's desired behavior, but also made it clear that a conventional, keyframed approach was not feasible. The team made a pivotal decision to shift their thinking from "how to animate the Huddle" to "how to simulate it." This move towards a physics-driven core was essential for achieving the emergent, unpredictable, and weighty behavior that the initial vision demanded.

The final Huddle is not animated in the traditional sense. It is a skinned mesh whose bones are directly bound to a collection of dynamic bodies being stepped by a custom physics engine developed by Thomas Cole. Every frame, the Huddle's core reads and analyzes the world, generates a multitude of internal impulses, and syncs them back to the physics engine. This custom model is built from several distinct, interacting components:

- Dynamic Bodies: The base layer consists of 26 rigid bodies that live and are governed by the physics engine. These form the creature's underlying physical mass.

- Internal Bones: A parallel structure of internal bones caches the properties (position, velocity, etc.) of the dynamic bodies. This layer is responsible for accumulating the internal impulses that are then fed back into the physics simulation.

- Adjacency Graph:

- At boot-up, the dynamic bodies are initially placed on a sphere, and an adjacency graph is established to connect the closest neighboring internal bones with edges that function as springs.

- The target length of these springs deforms constantly based on the core's overall scale and height. This allows the creature to realistically stretch, squash, and contort its body in response to forces.

- Spine Bones:

- Two central spine bones are driven not only by physics but also by logic and animation. They serve as the macro-level control system.

- Each spine bone influences a cluster of internal bones, forcing them to follow its general motion. This critical function allows the game's logic to direct the Huddle's overall movement, effectively "skimming the physics" to guide the simulation without overriding it.

A specific technical challenge highlighted the sophistication of this system: getting the Huddle back on its feet after it falls. Simply rotating the spine to a vertical position would look artificial and "a little bit silly." The solution was to reconfigure the spine bones at runtime, causing the entire internal structure to rise vertically in a more organic way. To avoid a jarring visual "pop" during this reconfiguration, the team cleverly blended the target edge lengths of the internal mesh over several frames, masking the transition and preserving the creature's believable physicality.

Ultimately, the Huddle's core is a complex network of largely independent systems—logic states, player control inputs, and auxiliary systems—all feeding impulses into a central, physics-driven structure. This architecture makes the final result ripe for unpredictable, emergent behavior, ensuring that no two interactions with the Huddle feel exactly the same. But this intricate, invisible core was only half the battle; the next step was to give it tangible limbs that could interact with the world.

3. The Illusion of Life: Procedural Limbs and Gameplay Integration

While the physics core provided dynamic and weighty movement, visually it appeared as an unconvincing "floating blob." To illustrate the problem, gameplay programmer Søren Trautner Madsen points to a simple analogy: a picture of a bird. Draw two crude stick arms on it, and as he puts it, "all of a sudden it's an entirely different creature." The next critical layer of development was to perform this same transformative trick on the Huddle—to ground its abstract physics in reality by creating the illusion of intentional locomotion through a clever procedural system for its limbs.

Madsen was given a clear mandate: add a thin visual layer of arms and legs without touching the constantly evolving core physics model. The solution was to treat the Huddle's appendages as separate meshes attached at runtime, forming a composite creature.

- Six static legs are attached to physics balls at the bottom of the core, responsible for locomotion.

- Six static arms are positioned at the top. They reconfigure themselves as the Huddle turns to maintain a consistent and readable silhouette.

- Numerous purely visual body parts (heads, torsos) are attached to the front surface, adding secondary motion and a sense of internal life.

- Several dynamic arms, normally hidden within the mass, can shoot out to assist in grabbing and interacting with objects.

The system used to animate the legs is a brilliant lie, a deceptively simple solution that Madsen admits he is "a bit embarrassed" to present because of its simplicity. It relies on a minimal set of just four running animations (two forward, two backward). The algorithm is a masterclass in elegant, efficient design:

- A raycast from the leg's attachment point on the core determines the precise ground position.

- The running animations are blended based on the leg's current distance from that ground position.

- The velocity of the parent physics body is mapped directly to the run cycle's animation speed, making the legs' movement perfectly match the core's momentum.

- Additional logic handles blending to a grounded pose when stopped, syncing leg positions for different gaits (walking vs. galloping), and freezing the animation to create a convincing sliding effect on slippery surfaces.

A similar procedural approach governs the arms, which are responsible for grabbing and interacting with the environment. This is managed by the "Aim Point" system:

- Each arm has a desire to reach an autonomous "aim point" that floats around the Huddle.

- A central "Arm Manager" identifies interesting objects in the scene, such as a crate, and assigns these aim points to specific grab-locations on that object.

- When an arm's aim point gets close enough to its target, the arm plays a grab animation and attaches. This allows the static and dynamic arms to convincingly grab, hold, and climb on objects, transforming a simple physics interaction into what appears to be a deliberate, intelligent action.

This procedural approach was a resounding success precisely because it was a brilliant solution to a tough constraint. The complex, believable locomotion is an illusion created by a simple visual system layered on top of the physics simulation, never interfering with it. This exemplifies a core tenet of Playdead's development philosophy: "generally we tweaked the Huddle as much as we could for the gameplay we needed and if we couldn't swing it enough we removed the gameplay and made some other gameplay where the system worked." The final challenge was to make these disparate, independently moving parts look and feel like they belonged to a single, unified organism.

4. The Shader as Glue: Unifying a Monstrosity

The final and perhaps most crucial challenge was to visually unify the Huddle's disparate elements—the core physics mesh, the procedural limbs, and the decorative body parts—into a single, cohesive creature. This task fell to the shader work of Mikkel Svendsen, which served as the "shader glue" to fuse the collection of independent geometries into one grotesque organism.

The artistic inspirations for the Huddle's surface were a study in contrasts. The lumpy, fleshy sculptures of John Isaacs provided a reference for form, while the colorful, multi-toned skin palettes in paintings by Rembrandt and Jenny Saville inspired a look that was organic and complex, avoiding simple pink flesh tones.

This vision was realized through a sophisticated, multi-layered shading pipeline, with each technique serving to glue the parts together:

-

Normals: Blending Hard and Soft

- To glue the hard-surfaced limbs to the soft-surfaced core, the shader blends the model's hard-edged normals with soft, sphere-projected normals. This technique dissolves the seams by preserving detail in the fingers and feet while ensuring the main body feels like a single, vague, and fleshy mass.

- To glue the hard-surfaced limbs to the soft-surfaced core, the shader blends the model's hard-edged normals with soft, sphere-projected normals. This technique dissolves the seams by preserving detail in the fingers and feet while ensuring the main body feels like a single, vague, and fleshy mass.

-

Lighting and Occlusion: Creating Depth

- An ambient term ensures visibility, layered with AO decals to subtract light, a baked crease texture for definition, and a crucial vertical gradient that creates self-occlusion from top to bottom, grounding the massive form.

- An ambient term ensures visibility, layered with AO decals to subtract light, a baked crease texture for definition, and a crucial vertical gradient that creates self-occlusion from top to bottom, grounding the massive form.

-

Diffuse Lighting: Character and Style

- A custom lighting model includes an exponential tonemap to prevent bright lights from washing out detail, a rim light for separation, a faked backlighting effect (internally called "roughness"), and a smooth toon-style step to enhance contrast.

-

Specular Highlights: Faking Wetness

- The specular highlight is a "total lie." It is not generated by scene lights but by a fake, hard-coded lighting direction (top, back, sides). This fake highlight is then masked by the actual incoming diffuse light, ensuring it only appears where the creature is lit. A "chicken skin" normal map is applied exclusively to this specular layer to achieve a greasy, "Saturday night chicken roast" appearance.

-

Subsurface Scattering: The Meaty Look

- A naive but highly effective approach to SSS gives the creature its fleshy translucence. It’s a four-sample spiral blur of the lighting buffer, colored red. To solve the common problem of light bleeding (e.g., from a hand to the chest, or the floor to the body), each sample is validated against both the depth buffer and a "huddle stencil buffer" to ensure it's sampling from the creature itself.

Beyond the base appearance, a dynamic surface effects system was created to visually reflect gameplay abuse. A script "listens" for collision or trigger events on the artist's "nine favorite rigid bodies" within the core. This CPU-side data (e.g., "this part was hit by a crane" or "this part is near a fire") is then gathered on the GPU to create a low-frequency mask that blends in bruise, burn, or blood textures in real-time.

Together, these shading techniques masterfully concealed the seams between the independent geometric parts, physics objects, and procedural systems. This shader glue transformed a collection of mechanical components into a single, believable, and deeply unsettling biological entity.

Conclusion: Emergence Through Collaboration

The Huddle is a powerful testament to the creative potential of long-term, iterative, and deeply collaborative design. Its six-year journey from a static drawing to a living, breathing entity showcases a process where artistic vision and technical execution were inseparable partners.

It began with a foundational "potato drawing" and concept animations that set a clear vision. This vision was then realized not through traditional methods, but through the engineering of a core physics simulation that gave the creature an unpredictable soul. That core was then dressed in a clever illusion of life with procedural limbs, making it appear to run, climb, and grab with intention. Finally, a sophisticated, multi-layered shader served as the ultimate glue, unifying these disparate systems into a single, cohesive, and grotesque organism.

The Huddle's final character was not designed by a single person or a single discipline. Instead, it emerged from the complex, and at times unpredictable, interaction of systems built by many different specialists over the better part of a decade. It is a true monster of emergence, born from the collective imagination of an entire studio.

L-My Words

L-Zotero citation key

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gFkYjAKuUCE

To be permanent notes (Complete Ideas)

P-Self Explained Sentences

P-Connection

- Parent

- Caused by::

- - Driven by::

- - Cite from::

-

- Caused by::

- Child

- Excalidraw::

- - Is source of::

- - Including::

- - Have Example::

- - Contributes to::

- - Consist of::

-

- Excalidraw::

- Friend

- Left

- Achieved with::

- - Affected by::

- - Supported by::

- - Enhanced by::

- - related::

-

- Achieved with::

- Right

- against::

- - Opposites::

-

- against::

- Left